When we were recently talking to Peter Thommen, a board builder who not long ago could keep up with Bjorn Dunkerbeck in a straight line, he remarked that nowadays he loathes to sail a fast slalom board in really powered conditions. Modern boards and sails are capable of such high speeds in rough conditions that it can be frightening: one small mistake—spinning out, dropping a rail, catching a gust under the nose—can mean a quick and painful end to the day. It can even mean serious injury. So, he’d rather hop on some freeride gear and enjoy a less demanding session.

HE’S NOT ALONE. As race boards and sails become faster and faster, fewer and fewer sailors find they want, or are even able, to sail the fastest stuff.

That’s one of the reasons we are focusing here on big sails. In 8 to 18-mph winds we can sail in control and detect differences that can be attributed to the design or tuning of the sails. In stronger winds the tendency is to see differences in sailors, not sails. One tester will make a mistake during a head-to-head run, the other will make a mistake during the next run, and the conclusions will be totally messed up.

We also stick with big sails because race sails are the most stable sails, and the biggest sail in a quiver should always be the most stable. That is, if you have only one race sail in your quiver, make it the biggest one.

Especially heavier sailors, should consider a race sail for the biggest sail in their quiver, as this is where one really good sail (and mast and boom) can take the place of two or three mediocre ones.

What should you look for in a race sail? We like the Aerotech Course VMG for longboards and very heavy sailors who want the ultimate in low-end power. This sail has guts and can be used on both racing longboards and wide shortboards.

For all-around fast performance and user-friendly rigging, the Sailworks X-T Racing and WindWing Race CS are hard to beat. We particularly like the fact that the Race CS is flat and thus able to handle a lot of wind, yet somehow also manages to muster plenty of power in the light stuff. The X-T has a lighter, crisper feel and the Race CS has the heavier construction.

Advertisement

For uncompromising performance and unimpeachable World Cup pedigrees, we have to like the Neil Pryde RX1 and North Sails IQ 3D. These are radically different sails: draft forward vs. draft back, lots of stiff battens vs. few, lots of static draft vs. little, plenty of luff curve vs. relatively little, moderate downhaul requirements vs. hernia city. One thing they do have in common is that neither is particularly easy to rig. They have slightly different strengths on a course, yet they’re both ripping fast.

Aerotech Course VMG

Longboards don’t generally hit the same high speeds that short raceboards do, so the sails for racing longboards are a bit different. There’s less emphasis on minimizing drag and more of a focus on maximizing power. That, in short, explains why the Course VMG is such an incredibly deep, powerful, tight-leeched sail. Longboards need that power. Compared to big sails from just five years ago, the Course VMG is probably no more powerful, but it’s lighter, easier to rig and easier to sail on a shortboard. In fact, we sailed it extensively on wide shortboards, like the Pro-Tech 290 C.A.T. and found it not only remarkably quick to power up, but also manageable in the 12-mph gusts. Light-air longboard racers and heavyweights looking to plane off in minimum winds can’t go wrong with this sail.

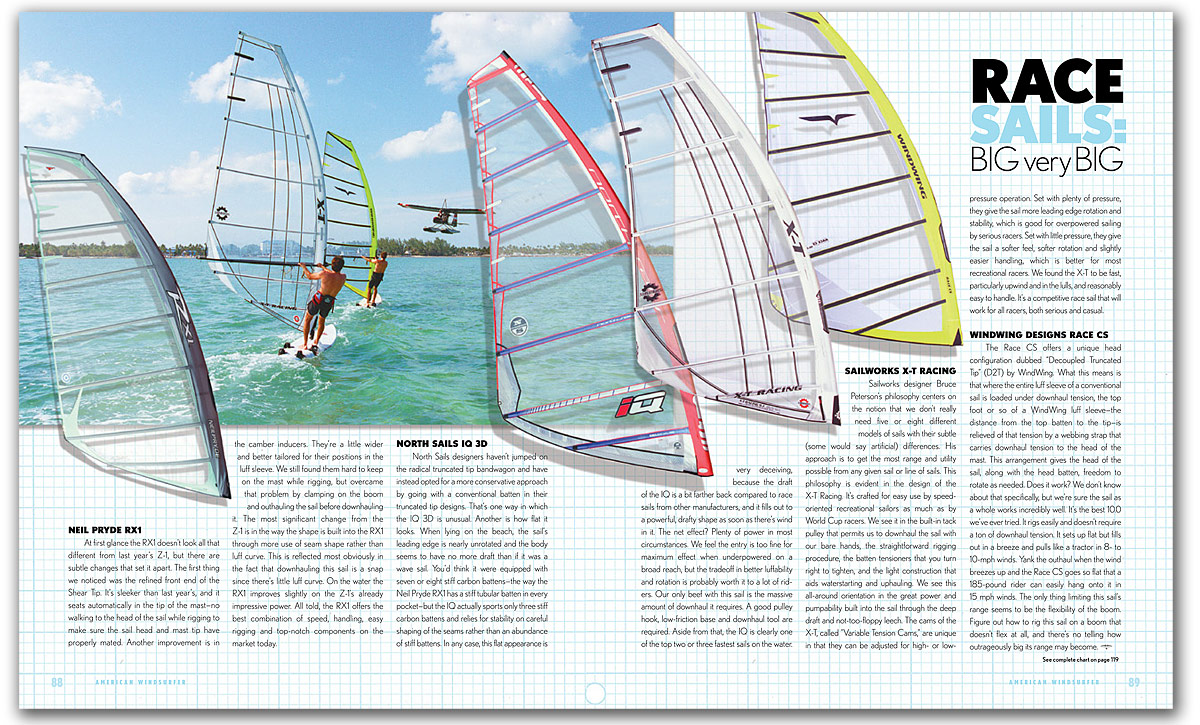

Neil Pryde RX1

At first glance the RX1 doesn’t look all that different from last year’s Z-1, but there are subtle changes that set it apart. The first thing we noticed was the refined front end of the Shear Tip. It’s sleeker than last year’s, and it seats automatically in the tip of the mast—no walking to the head of the sail while rigging to make sure the sail head and mast tip have properly mated. Another improvement is in the camber inducers. They’re a little wider and better tailored for their positions in the luff sleeve. We still found them hard to keep on the mast while rigging, but overcame that problem by clamping on the boom and outhauling the sail before downhauling it. The most significant change from the Z-1 is in the way the shape is built into the RX1 through more use of seam shape rather than luff curve. This is reflected most obviously in the fact that downhauling this sail is a snap since there’s little luff curve. On the water the RX1 improves slightly on the Z-1’s already impressive power. All told, the RX1 offers the best combination of speed, handling, easy rigging and top-notch components on the market today.

North Sails IQ 3D

North Sails designers haven’t jumped on the radical truncated tip bandwagon and have instead opted for a more conservative approach by going with a conventional batten in their truncated tip designs. That’s one way in which the IQ 3D is unusual. Another is how flat it looks. When lying on the beach, the sail’s leading edge is nearly unrotated and the body seems to have no more draft than if it was a wave sail. You’d think it were equipped with seven or eight stiff carbon battens—the way the Neil Pryde RX1 has a stiff tubular batten in every pocket—but the IQ actually sports only three stiff carbon battens and relies for stability on careful shaping of the seams rather than an abundance of stiff battens. In any case, this flat appearance is very deceiving, because the draft of the IQ is a bit farther back compared to race sails from other manufacturers, and it fills out to a powerful, drafty shape as soon as there’s wind in it. The net effect? Plenty of power in most circumstances. We feel the entry is too fine for maximum effect when underpowered on a broad reach, but the tradeoff in better luffability and rotation is probably worth it to a lot of riders. Our only beef with this sail is the massive amount of downhaul it requires. A good pulley hook, low-friction base and downhaul tool are required. Aside from that, the IQ is clearly one of the top two or three fastest sails on the water.

Sailworks X-T RaciNG

Sailworks designer Bruce Peterson’s philosophy centers on the notion that we don’t really need five or eight different models of sails with their subtle (some would say artificial) differences. His approach is to get the most range and utility possible from any given sail or line of sails. This philosophy is evident in the design of the X-T Racing. It’s crafted for easy use by speed-oriented recreational sailors as much as by World Cup racers. We see it in the built-in tack pulley that permits us to downhaul the sail with our bare hands, the straightforward rigging procedure, the batten tensioners that you turn right to tighten, and the light construction that aids waterstarting and uphauling. We see this all-around orientation in the great power and pumpability built into the sail through the deep draft and not-too-floppy leech. The cams of the X-T, called “Variable Tension Cams,” are unique in that they can be adjusted for high- or low-pressure operation. Set with plenty of pressure, they give the sail more leading edge rotation and stability, which is good for overpowered sailing by serious racers. Set with little pressure, they give the sail a softer feel, softer rotation and slightly easier handling, which is better for most recreational racers. We found the X-T to be fast, particularly upwind and in the lulls, and reasonably easy to handle. It’s a competitive race sail that will work for all racers, both serious and casual.

Advertisement

Windwing Designs Race CS

The Race CS offers a unique head configuration dubbed “Decoupled Truncated Tip” (D2T) by WindWing. What this means is that where the entire luff sleeve of a conventional sail is loaded under downhaul tension, the top foot or so of a WindWing luff sleeve—the distance from the top batten to the tip—is relieved of that tension by a webbing strap that carries downhaul tension to the head of the mast. This arrangement gives the head of the sail, along with the head batten, freedom to rotate as needed. Does it work? We don’t know about that specifically, but we’re sure the sail as a whole works incredibly well. It’s the best 10.0 we’ve ever tried. It rigs easily and doesn’t require a ton of downhaul tension. It sets up flat but fills out in a breeze and pulls like a tractor in 8- to 10-mph winds. Yank the outhaul when the wind breezes up and the Race CS goes so flat that a 185-pound rider can easily hang onto it in 15 mph winds. The only thing limiting this sail’s range seems to be the flexibility of the boom. Figure out how to rig this sail on a boom that doesn’t flex at all, and there’s no telling how outrageously big its range may become.

Have something to add to this story? Share it in the comments.