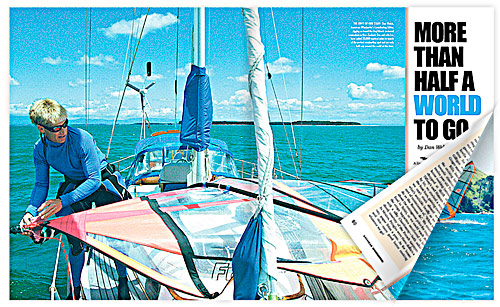

THE ENVY OF OUR STAFF: Dan Welch, American Windsurfer’s Contributing Editor, rigging on board the Dag’Attack anchored somewhere in New Zealand. Dan and wife Liz, have sailed 30,000 nautical miles in search of the perfect windsurfing spot and are only half way around the world at this time.

“Hey buddy, you need a tow?” A line was tossed and I snatched it.

Ah crap, how embarrassing. I had just launched from the Floridian shore to windsurf around the world, and promptly ran aground. No problem, I thought—wade into deeper water, hop aboard, and sheet in. No problem, except that when my fin is stuck in the mud, my board draws seven feet and weighs nineteen tons. I stood beside it, unable to breathe, tugging at the sunken weight, with a long way to venture ahead of me. This was only the beginning.

My big board carrier, the mothership, is a forty–foot cutter-rigged sailboat named Daq’Attack. Four satellite boards are strapped to her deck; the forecabin is choked with sails, booms, fins, and all spare parts necessary to repair the gear because, where we’re headed, no one accepts American Express.

AS FOR BEANS AND RICE

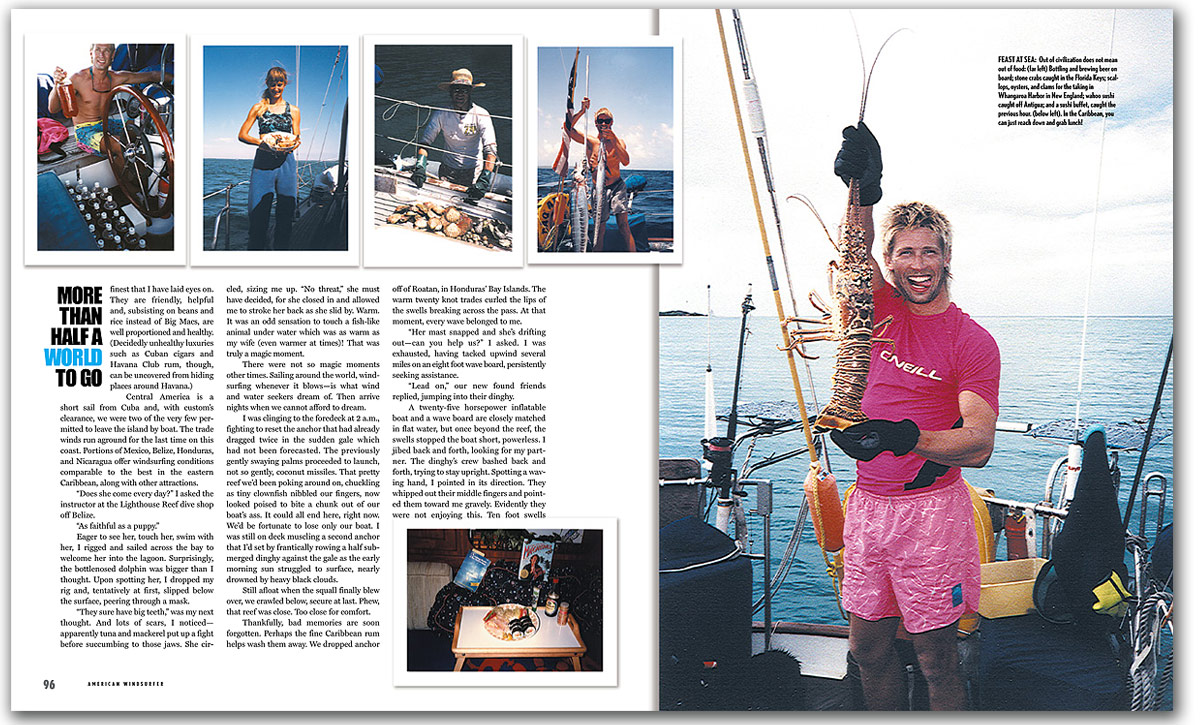

“No phone, no lights, no motorcar”, and infrequent luxuries, make the cruising lifestyle possible for us. HAM radio keeps us in touch (and its doesn’t ring!), wind and solar power illuminate our cabin; our dinghy’s eight horses sip gasoline; and occasionally a nice yellowfin impales itself on my hook in time for sushi dinner. Why would Gilligan ever want to leave? And, Ginger married me.Bills, leases, and loans gobble up the cruising kitty, so we set a course towards elimination date. I drove a twelve year old Toyota to death; we ate home cooking instead of fancy fare; we shopped at thrift stores instead of Tiffany’s and Neiman-Marcus; and, bit by bit, we stocked a surplus to pay off the boat loan, gaining ownership. What we can’t stock aboard we purchase what’s available locally as we now sail, sort of reminiscent of, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do”. We could bitch about the outrageous price for imported food in Tahiti, or we could wash down the crispy baguettes smothered in brie with a silky Chardonnay—both subsidized, courtesy of the French taxpayer. In Mexico, Pringles were three dollars a can, papas fritas a peso. As for beans and rice—more good home cooking wherever we go!

Dreams of windsurfing around the world charted my course ever since my siblings and I blew all our snow shoveling and leaf raking profits to purchase our first set of teak booms, back in the infant days of windsurfing. (I just gave away my age).

Since then, I focused on this goal—but not in a crazy way. I remember suffering through a daytime talk show once, to hear from an insane Frenchman who had windsurfed alone across the Atlantic. To shock the listening crowd with his heroism, he grasped one hand by the other and pulled—his tendons stretched like a bungee cord since they’d been permanently deformed by 50-odd days of hanging on at sea.

That was not how I wanted to adventure. I wanted to enjoy a few luxuries such as basic food and water, perhaps a case of rum or two, my lovely wife. A non-stop windsurfing adventure was ahead in my plan but included breaks from the boom. After being dragged into

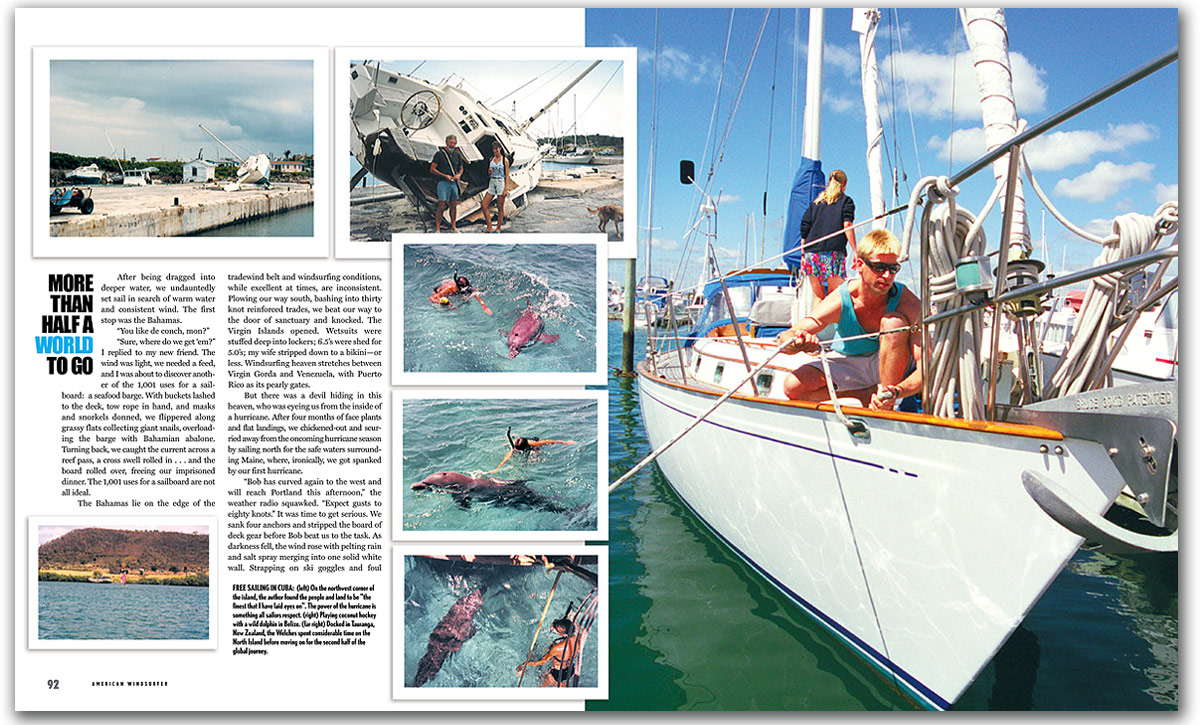

After being dragged into deeper water, we undauntedly set sail in search of warm water and consistent wind. The first stop was the Bahamas.“You like de conch, mon?”

“Sure, where do we get ‘em?” I replied to my new friend. The wind was light, we needed a feed, and I was about to discover another of the 1,001 uses for a sailboard: a seafood barge. With buckets lashed to the deck, tow rope in hand, and masks and snorkels donned, we flippered along grassy flats collecting giant snails, overloading the barge with Bahamian abalone. Turning back, we caught the current across a reef pass, a cross swell rolled in . . . and the board rolled over, freeing our imprisoned dinner. The 1,001 uses for a sailboard are not all ideal.

The Bahamas lie on the edge of the tradewind belt and windsurfing conditions, while excellent at times, are inconsistent. Plowing our way south, bashing into thirty knot reinforced trades, we beat our way to the door of sanctuary and knocked. The Virgin Islands opened. Wetsuits were stuffed deep into lockers; 6.5’s were shed for 5.0’s; my wife stripped down to a bikini—or less. Windsurfing heaven stretches between Virgin Gorda and Venezuela, with Puerto Rico as its pearly gates.

FREE SAILING IN CUBA: (left) On the northwest corner of the island, the author found the people and land to be “the finest that I have laid eyes on”. The power of the hurricane is something all sailors respect. (right) Playing coconut hockey with a wild dolphin in Belize. (far right) Docked in Tauranga, New Zealand, the Welches spent considerable time on the North Island before moving on for the second half of the global journey.

But there was a devil hiding in this heaven, who was eyeing us from the inside of a hurricane. After four months of face plants and flat landings, we chickened-out and scurried away from the oncoming hurricane season by sailing north for the safe waters surrounding Maine, where, ironically, we got spanked by our first hurricane.

“Bob has curved again to the west and will reach Portland this afternoon,” the weather radio squawked. “Expect gusts to eighty knots.” It was time to get serious. We sank four anchors and stripped the board of deck gear before Bob beat us to the task. As darkness fell, the wind rose with pelting rain and salt spray merging into one solid white wall. Strapping on ski goggles and foul weather gear, I motored ahead to reduce strain on the anchor ropes, already screeching like tense guitar strings. The dinghy corkscrewed in mid-air on its tether behind the boat, until the line detonated and our life board disappeared in the white-out, along with a neighboring yacht dragging its mooring—two tons of well buried locomotive wheels. There is such a thing as too much wind after all.

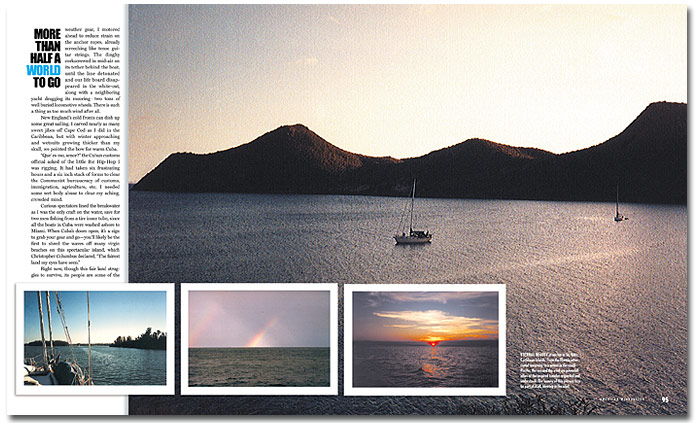

New England’s cold fronts can dish up some great sailing. I carved nearly as many sweet jibes off Cape Cod as I did in the Caribbean, but with winter approaching and wetsuits growing thicker than my skull, we pointed the bow for warm Cuba.

“Que’ es eso, senor?” the Cuban customs official asked of the little Bic Hip-Hop I was rigging. It had taken six frustrating hours and a six-inch stack of forms to clear the Communist bureaucracy of customs, immigration, agriculture, etc. I needed some wet body abuse to clear my aching, crowded mind.

Curious spectators lined the breakwater as I was the only craft on the water, save for two men fishing from a tire inner tube, since all the boats in Cuba were washed ashore to Miami. When Cuba’s doors open, it’s a sign to grab your gear and go—you’ll likely be the first to shred the waves off many virgin beaches on this spectacular island, which Christopher Columbus declared, “The fairest land my eyes have seen.”

Right now, though this fair land struggles to survive, its people are some of the finest that I have laid eyes on. They are friendly, helpful and, subsisting on beans and rice instead of Big Macs, are well proportioned and healthy. (Decidedly unhealthy luxuries such as Cuban cigars and Havana Club rum, though, can be uncovered from hiding places around Havana.)

Central America is a short sail from Cuba and, with custom’s clearance, we were two of the very few permitted to leave the island by boat. The trade winds run aground for the last time on this coast. Portions of Mexico, Belize, Honduras, and Nicaragua offer windsurfing conditions comparable to the best in the eastern Caribbean, along with other attractions.

ETERNAL BEAUTY at anchor in St. Kitts, Caribbean Islands. From the Florida intercostal waterway to a sunset in the south Pacific, the sea and the wind are powerful allies of the inspired traveler respected and understood. The beauty of this journey is to be part of it all, blowing in the wind.

“Does she come every day?” I asked the instructor at the Lighthouse Reef dive shop off Belize.

“As faithful as a puppy.”

Eager to see her, touch her, swim with her, I rigged and sailed across the bay to welcome her into the lagoon. Surprisingly, the bottlenosed dolphin was bigger than I thought. Upon spotting her, I dropped my rig and, tentatively, at first, slipped below the surface, peering through a mask.

“They sure have big teeth,” was my next thought. And lots of scars, I noticed—apparently tuna and mackerel put up a fight before succumbing to those jaws. She circled, sizing me up. “No threat,” she must have decided, for she closed in and allowed me to stroke her back as she slid by. Warm. It was an odd sensation to touch a fish-like animal under water which was as warm as my wife (even warmer at times)! That was truly a magic moment.

There were not so magic moments other times. Sailing around the world, windsurfing whenever it blows—is what wind and water seekers dream of. Then arrive nights when we cannot afford to dream.

FEAST AT SEA: Out of civilization does not mean out of food: (far left) Bottling and brewing beer on board; stone crabs caught in the Florida Keys; scallops, oysters, and clams for the taking in Whangaroa Harbor in New England; wahoo sushi caught off Antigua; and a sushi buffet, caught the previous hour. (below left). In the Caribbean, you can just reach down and grab lunch!

I was clinging to the foredeck at 2 a.m., fighting to reset the anchor that had already dragged twice in the sudden gale which had not been forecasted. The previously gently swaying palms proceeded to launch, not so gently, coconut missiles. That pretty reef we’d been poking around on, chuckling as tiny clownfish nibbled our fingers, now looked poised to bite a chunk out of our boat’s ass. It could all end here, right now. We’d be fortunate to lose only our boat. I was still on deck muscling a second anchor that I’d set by frantically rowing a half submerged dinghy against the gale as the early morning sun struggled to surface, nearly drowned by heavy black clouds.

Still afloat when the squall finally blew over, we crawled below, secure at last. Phew, that reef was close. Too close for comfort.

Thankfully, bad memories are soon forgotten. Perhaps the fine Caribbean rum helps wash them away. We dropped anchor off of Roatan, in Honduras’ Bay Islands. The warm twenty-knot trades curled the lips of the swells breaking across the pass. At that moment, every wave belonged to me.

“Her mast snapped and she’s drifting out—can you help us?” I asked. I was exhausted, having tacked upwind several miles on an eight-foot wave board, persistently seeking assistance.

“Lead on,” our new found friends replied, jumping into their dinghy.

A twenty-five horsepower inflatable boat and a wave board are closely matched in flat water, but once beyond the reef, the swells stopped the boat short, powerless. I jibed back and forth, looking for my partner. The dinghy’s crew bashed back and forth, trying to stay upright. Spotting a waving hand, I pointed in its direction. They whipped out their middle fingers and pointed them at me gravely. Evidently they were not enjoying this. Ten-foot swells rolled across the deeply submerged reef surrounding one of Panama’s San Blas Islands and, though not breaking, they were stacking up and scaring the crap out of these local rescuers. However, they struggled to get my wife and her gear aboard and, by the time I’d beaten back to the boats again, were already well lubed with Panamanian Anejo, and willing to forgive with a post-heroic high mixed with relief, I suppose.

We left the Caribbean unobtrusively by the rear exit, this time, threading the Panama Canal en route to the Pacific. As the last chamber’s doors groaned, the other side of the world opened before us. Unfortunately, the wind closed—Panama’s mountains unplug the tradewind machine. We headed west.

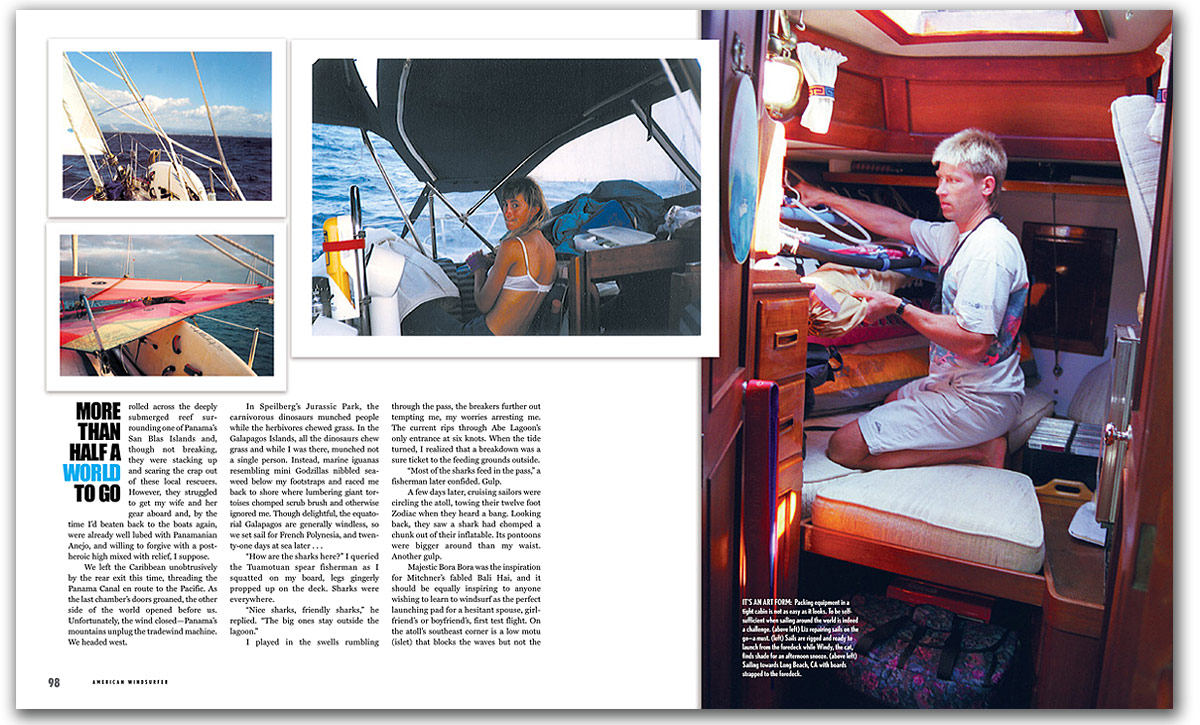

IT’S AN ART FORM: Packing equipment in a tight cabin is not as easy as it looks. To be self-sufficient when sailing around the world is indeed a challenge. (above left) Liz repairing sails on the go—a must. (left) Sails are rigged and ready to launch from the foredeck while Windy, the cat, finds shade for an afternoon snooze. (above left) Sailing towards Long Beach, CA with boards strapped to the foredeck.

In Speilberg’s Jurassic Park, the carnivorous dinosaurs munched people while the herbivores chewed grass. In the Galapagos Islands, all the dinosaurs chew grass and while I was there, munched not a single person. Instead, marine iguanas resembling mini Godzillas nibbled seaweed below my footstraps and raced me back to shore where lumbering giant tortoises chomped scrub brush and otherwise ignored me. Though delightful, the equatorial Galapagos are generally windless, so we set sail for French Polynesia and twenty-one days at sea later . . .

“How are the sharks here?” I queried the Tuamotuan spear fisherman as I squatted on my board, legs gingerly propped up on the deck. Sharks were everywhere.

“Nice sharks, friendly sharks,” he replied. “The big ones stay outside the lagoon.”

I played in the swells rumbling through the pass, the breakers further out tempting me, my worries arresting me. The current rips through Abe Lagoon’s only entrance at six knots. When the tide turned, I realized that a breakdown was a sure ticket to the feeding grounds outside.

“Most of the sharks feed in the pass,” a fisherman later confided. Gulp.

A few days later, cruising sailors were circling the atoll, towing their twelve foot Zodiac when they heard a bang. Looking back, they saw a shark had chomped a chunk out of their inflatable. Its pontoons were bigger around than my waist. Another gulp.

Majestic Bora Bora was the inspiration for Mitchner’s fabled Bali Hai, and it should be equally inspiring to anyone wishing to learn to windsurf as the perfect launching pad for a hesitant spouse, girlfriend’s or boyfriend’s, first test flight. On the atoll’s southeast corner is a low motu (islet) that blocks the waves but not the wind. Therefore, it blocks the danger but not the fun. Adding to the fun, at its small resort, nearly all that the French ladies wear is sunblock.

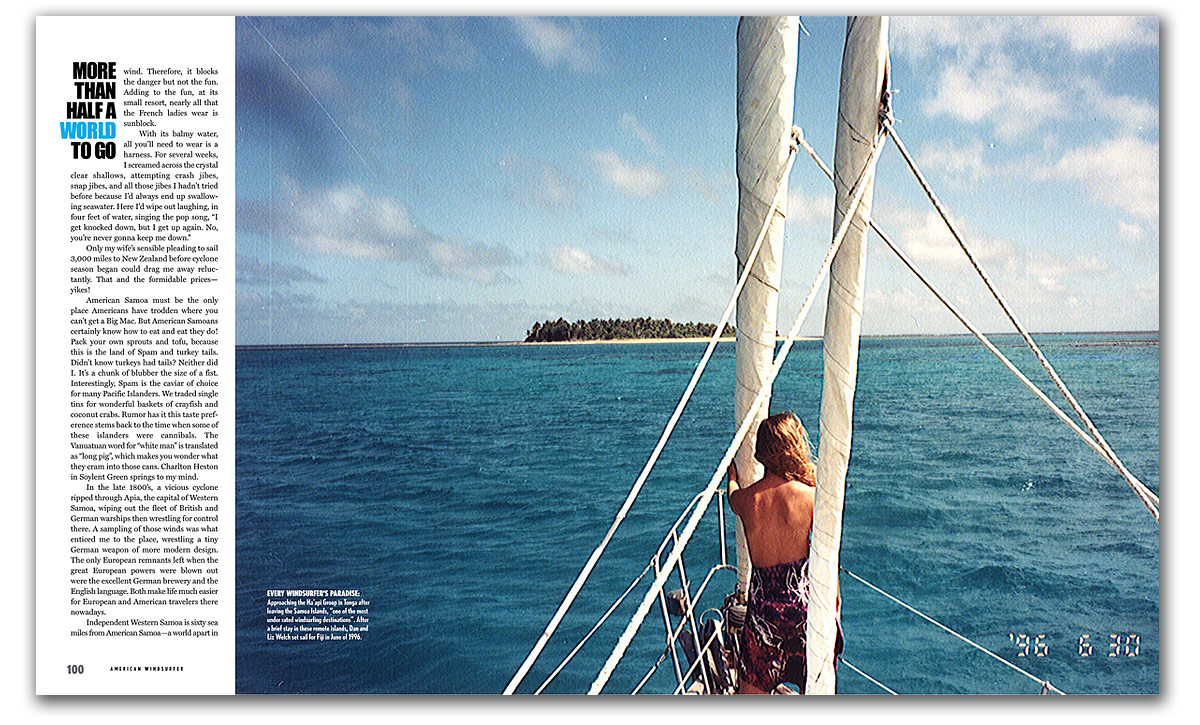

EVERY WINDSURFER’S PARADISE: Approaching the Ha’api Group in Tonga after leaving the Samoa Islands, “one of the most under rated windsurfing destinations”. After a brief stay in these remote islands, Dan and Liz Welch set sail for Fiji in June of 1996.

With its balmy water, all you’ll need to wear is a harness. For several weeks, I screamed across the crystal clear shallows, attempting crash jibes, snap jibes, and all those jibes I hadn’t tried before because I’d always end up swallowing seawater. Here I’d wipe out laughing, in four feet of water, singing the pop song, “I get knocked down, but I get up again. No, you’re never gonna keep me down.”

Only my wife’s sensible pleading to sail 3,000 miles to New Zealand before cyclone season began could drag me away reluctantly. That and the formidable prices—yikes!

American Samoa must be the only place Americans have trodden where you can’t get a Big Mac. But American Samoans certainly know how to eat and eat they do! Pack your own sprouts and tofu, because this is the land of Spam and turkey tails. Didn’t know turkeys had tails? Neither did I. It’s a chunk of blubber the size of a fist. Interestingly, Spam is the caviar of choice for many Pacific Islanders. We traded single tins for wonderful baskets of crayfish and coconut crabs. Rumor has it this taste preference stems back to the time when some of these islanders were cannibals. The Vanuatuan word for “white man” is translated as “long pig”, which makes you wonder what they cram into those cans. Charlton Heston in Soylent Green springs to my mind.

Advertisement

In the late 1800’s, a vicious cyclone ripped through Apia, the capital of Western Samoa, wiping out the fleet of British and German warships then wrestling for control there. A sampling of those winds was what enticed me to the place, wrestling a tiny German weapon of more modern design. The only European remnants left when the great European powers were blown out were the excellent German brewery and the English language. Both make life much easier for European and American travelers there nowadays.

Independent Western Samoa is sixty sea miles from American Samoa—a world apart in reality and one of the most underrated windsurfing destinations I’ve stumbled upon. As the Pacific swells wrap around the island of Upolu, they expend their remaining energy on Apia’s reefs. This orientation also diverts the trade winds to side-offshore. My short-board, followed by dozens of curious dark Samoan eyes, were the only things on the waves for the two months I sailed the remote waters.

“Wow, I was just windsurfing alongside a pilot whale!” I said to a guy rigging on the beach in Tauranga, on New Zealand’s North Island. “His fin was this high out of the water.” I extended my arms to exaggerate the fish story as is common and accepted with fishermen.

“We don’t get pilot whales here, mate. She’ll be a killer whale.”

Huh, killer whale?

Smelling my fright, he continued, “No worries. Never heard of them eating anyone.”

Yeah, and Tuamotuan sharks are friendly, and Melanesians prefer Spam.

Splashing around in a black rubber suit, sprawled on the board with arms dangling, I had every characteristic of something delectably edible for a killer whale. Yes, I’m a chicken of the sea but uneaten as of yet, and hoping to stay that way.

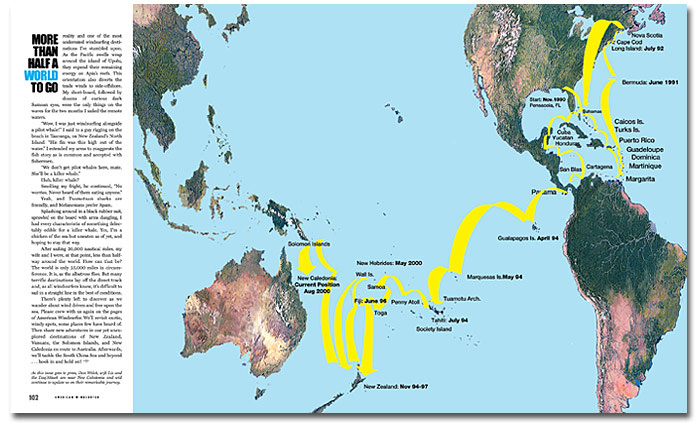

After sailing 30,000 nautical miles, my wife and I were, at that point, less than halfway around the world. How can that be? The world is only 25,000 miles in circumference. It is, as the albatross flies. But many terrific destinations lay off the direct track and, as all windsurfers know, it’s difficult to sail in a straight line in the best of conditions.

There’s plenty left to discover as we wander about wind driven and free upon the sea. Please crew with us again on the pages of American Windsurfer. We’ll revisit exotic, windy spots, some places few have heard of. Then share new adventures in our yet unexplored destinations of New Zealand, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, and New Caledonia en route to Australia. Afterwards, we’ll tackle the South China Sea and beyond . . . hook in and hold on!

As this issue goes to press, Dan Welch, wife Liz and the Daq’Attack are near New Caledonia and will continue to update us on their remarkable journey.