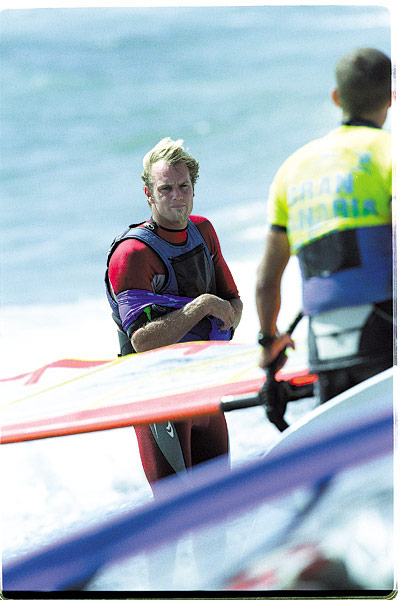

NEW WORLD CHAMPION: American Kevin Pritchard takes over as the PWA Overall World Champion from Bjorn Dunkerbeck. Only two other people in the history of windsurfing have held the title.

It was a matter of time before Bjorn Dunkerbeck would give up his Global Domination of windsurfing. Winning, for the twelve-time world champion had become as routine, as punching in and punching out of the yearly time clock at the Professional Windsurfing Association (PWA) World Tour. The routine has become so common place, that the tour, in recent years, has arguably suffered momentum as sponsors and competitors gathered like moss going nowhere.

But for two years, the window of opportunity started to crack open, Bjorn’s arsenal of board shapers; sail designers and fin makers were either tired, bored or dropped out. Dunkerbeck himself was not so fixed on winning all the time. In fact one might say that he’s gained a reputation as an extremely gracious loser. There were never excuses coming out of Bjorn’s mouth for losing a race, only congratulations and always a proud smile for the often-bewildered winner. Often times one could see Bjorn crossing the finish line behind another and a thumb up salute would be flashed towards the winner.

But twelve times was enough, and Bjorn knew it. He even said, “Number twelve is a good number.” But he couldn’t just walk away and give up the title by default. He wanted his successor to earn it.

Kevin Pritchard certainly earned the title and, in more ways than one. It took him and a team of sailors—including his older brother Matt—almost three years to de-throne Bjorn. When it happened, Bjorn was a true winner; gracious and as happy for Kevin’s achievement as everyone else was.

Nevertheless, an era has passed and Bjorn has stepped down. Those in the know would point out several unfair factors that brought down the Goliath. They suggest that the cards were quietly stacked against him through out the year. But such claims are not intended to discredit the young American whose mild mannered shyness and oh-shucks attitude could not be further from the former icy glare of the dominator.

In the brief history of professional windsurfing, Kevin Pritchard is only the third person, (the second American) to attain the Professional Overall World Champion Title. To achieve this, in years past, the winner had to excel in three disciplines: Waves, Slalom, and Course Racing. As far as windsurfing is concerned, you might as well be a champion in hockey, football, and soccer. Each one of these windblown disciplines is as different as the other. They not only require a different set of skills but completely different sets of equipment. It is bad enough to lug one load of equipment around the world—imagine lugging three times as much to compete in all disciplines.

Twenty four year old Kevin and older brother of Matt Pritchard— a contender for the title himself before breaking an ankle earlier this year in the Canaries—both had tough roads to the top. You could say their paths were marred by political and industry driven setbacks.

PASSING THE TORCH: A gracious Bjorn Dunkerbeck watches on as the NEW World Champion Kevin Pritchard accepts the award at the Aloha Classic on Maui this past November. (left) Aerial action at Fuerteventura and Pritchard sailing away to the overall win.

In a normal breathing American sport, the makers—the shakers—the corporate image-makers, find rising stars to invest time and money and dedicatedly mold them into heir apparent. In the case of the Pritchard brothers, they had three strikes against them. First, they were born in America. Second they are stars in a sport which hasn’t caught the fancy of Madison Avenue, thus the American appeal. And third, they are inseparable brothers. Where one goes, so goes the other.

While windsurfers may be no one in America; they are like Rock Stars in Europe. In France the sport is like basketball and in most of the European countries, it’s the number one sport that people want to try. So to have a World Champion who is European like Bjorn, whose parents are Danish, who lives in Spain and speaks umpteenth languages—sponsorship is good business.

The Pritchard brothers on the other hand, are harder to define. They are genuinely American and as sweet as apple pie. For many years, they bounced around from sponsor to sponsor, never finding solid support and sound business practices. But their talents never dimmed and they never soured their inbred sweetness.

Thus, the crowning of Kevin Pritchard as the World Champion is an achievement ever so deserving. The triumph also rewarded some gutsy business decisions that bucked the system and created a way to do things differently.

When the dominant sail sponsor Neil Pryde, (Bjorn’s key sponsor), declined to back the brothers as a pair, the brothers got together with a celebrated sail designer and two other well known World Cup sailors to form a group called “The Team”.

It was a novel idea at the time. Four World Cup racers and one sail designer would train as a team, design sails as a team, market themselves as a team, and even race as a team. Though racing as a team is not allowed in the PWA, their tactical nuances were hard to enforce. More than one racer on the world tour, felt the effect and complained about this obvious advantage. But the risk was high when The Team was formed. Neil Pryde, who might have thought at the time, that no other sail company could afford or was willing to sponsor a team concept, took a chance and offered Kevin a $180,000 individual package. Consequentially, the gamble failed. Kevin stuck to The Team and eventually, the group, (which included Phil McGain, Scott Fenton, and Barry Spanier) got picked up by Gaastra.

Advertisement

To make a long story short, Gaastra, an old Dutch sail brand who struggled through the early 90s and eventually was inherited by their Chinese manufacturing group. In a bold move, the new owner of Gaastra replaced their whole marketing group with The Team, for the reported sum of $400,000. Also Fiberspar, a composite mast and boom company came on as a non-paying rig support company. Now, The Team not only designs and races the products they also fill the marketing shoes of the sail company.

You might say that the triumph of the young American has all the twists and turns of a great American Novel. But there is an undeniable sense of hollowness to the win. Some might say that the win is tantamount to attaining the position of Captain on the Titanic. For this year, the PWA tour under a British management team, failed to deliver and maintain several world class events. The numbers of competitors on the tour has dropped significantly and organizers are having harder time finding sponsorships. Professional windsurfing has become too expensive, technically demanding and requires way too much wind to maintain.

For many, a new class called Formula was a prefect solution. It’s a class that restricts equipment and brings the wind requirement down to reasonable levels. Suddenly, as the future of the PWA began to waiver, a movement began to surface to lobby the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the International Sailing Federation (ISF) to replace the current IMCO Olympic windsurfing board for the Formula.

Just about the third week in November when Pritchard received the world title, members of the ISF met in Austria and voted to keep the IMCO class for the 2004 games. The predominant reason was that Formula racing, which requires a minimum 8+ knots of wind, would not have been suited for the Sydney games. Had Formula been there, only one day in the entire event would have been official. And, considering the IOC’s wish to trim back on the number of classes, windsurfing would have gotten an unfortunate quick boot out the door.

This failure came as a blow to many in the industry and the professional organizers. Formula was a lifeline, a bridge to a future for many of them. The IFS’s decision to keep an antiquated piece of equipment over the high performance, more representative Formula Class does shatters their hopes. But the decision pointed a sobering finger at just how far the industry leaders of the sport have moved away from their ultimate responsibility of growing a sport. They lost sight of reality and tried to catch the Olympics as a life raft. The decision was a clear—the message, “Return to the roots!”

It may be that Kevin Pritchard’s achievement symbolizes also a movement to the roots. Windsurfing grew out of a Southern Californian beach not far from the Pritchards home. It caught the world by storm and created an opportunity for the masses to have access and a dynamic social interaction with the elements. In the twelve years that Bjorn Duckerbeck rained, the sport became an arms race. Companies became shortsighted and followed the pied piper into technical suicide. But with the rise of the young American, who didn’t follow the ways of the industry, and achieved the title by doing it his way—maybe the times, they really are changing.

The failure of an industry can be as loud and destructive as the failure of one man who doesn’t take into account the consequences to ones’ action.

Windsurfing is an industry that has thrived on action and the intimate moments that can only be captured out on the water flying in a helicopter. Without this access, these dramatic displays, the icons of the sports, and the marketing of the performance side of the sport will vanish.

On Maui, where 95% of the windsurfing image-makers make their mark, a somewhat disgruntled and controversial windsurfer sat on the beach at Ho’okipa and took offense at the fact that a helicopter flew into his view and spoiled the ambiance for the moment.

Without warning to the photographer or the pilot, the man took pictures and posted on his website along with comments about how the helicopter treated those on the beach relating it to a “war zone clamor, complete with death defying danger.” At the same site, the man writes, “…your reporter has contacted the FAA regarding this most dangerous nuisance.”

Three week later, Peter Vorhes, the seasoned helicopter pilot who is instrumental for most of the air-to-sail photos you see of windsurfers, gets slapped with a notification that the FAA is conducting a review at the highest level. Suddenly the threat that the pilot could loose his license, grounded all flights for windsurfing photographers, including this magazine.

When told of this by the editor, the man claimed that he never told the FAA that the pilot was flying “recklessly and dangerous”. He claimed the FAA misinterpreted his words even though his website clearly stated that the pilot was flying dangerously.

When photographer Darrell Wong asked the man to recant his misleading complaint to the FAA, the man insisted that he would not do this unless he could leverage a meeting so that flights over Ho’okipa can be banned. No meetings are forthcoming and meanwhile, a good safe pilot sits on the ground fighting the nightmares of a bureaucracy to clear his name.

So we spin in this great circle of life.