I love the new Aerotech downhaul pulley. It’s low-profile and easy to use. But if you don’t have Aerotech sails and want an easy way to downhaul your sail, the Crankn’ PowerXtension is finally on the market in its final and fully functional form. This mast base with the built-in crank makes getting those last few inches of downhaul tension as easy as grinding pepper onto your five-green salad. And how about those new small-grip Fiberspar booms? Tiny grip and stiff, too. They’re much like the Windsurfing Hawaii carbon booms, except the front half—the entire front half—of the WH booms is a continuous carbon tube. Speaking of Windsurfing Hawaii, for next year they have an aluminum camlock buckle for their adjustable harness lines. We hear Dakine is coming out with something similar. Can’t wait to try them.

We have to give Fiberspar a lot of credit for going to a production method in which masts are built one half at a time. This permits buyers to match, say, any Tidal Wave bottom with any Tidal Wave top and reap the obvious financial benefits: No need to buy an entire new mast when only one half of the old one breaks.

Better yet, the new system allows customers to combine, say, a 30% carbon bottom with a 70% carbon top, for lower overall weight and better reflex response than an all–30% carbon mast would offer and better durability than all–70% carbon. This mix makes particular sense when you consider that most masts break at or below the boom and thus need to be tougher in the lower half.

Every year I see innovations like these and wish I had come up with them. Forehead-slap-entertaining though these new products may be, the real action for 1999—the changes that look like they’ll shape windsurfing for years to come—have to do with the same old themes: board and sail design and construction.

Sails: Construction

The trend in sail construction is toward more use of X-Ply cloths (See page 36) rather than straight monofilm. The standard monofilm that’s been used so widely over much of the last decade was, when introduced, a leap forward in sail stability, but it has never been as durable as the old Mylars and Dacrons it replaced. Once creased—and it’s easily creased—it can eventually crack along the crease line, and once punctured or cracked it allows tears to easily propagate. More importantly, ultra-violet radiation from the sun causes it to break down over time.

Sails: Design

The major trend in sail design continues toward truncated tips. Simmer and Gaastra started innovating in the tip of the sail a few years ago and now everyone’s doing it. Interestingly, the most conspicuously successful of the new tip designs—the Neil Pryde Z-1—is quite different from those original ones, and the original designs have either been abandoned or dramatically modified. Simmer’s new CyberRace–the sail Anders Bringdal used in the Trans-Atlantic race is now much like the Z-1 in tip design and the latest of the Gaastra Total Flow designs have less dramatically bent mast tip extensions. Gaastra designers are also trying to get away from the use of non-standard masts in it their Total Flow sails.

While the likes of Pryde, Simmer, Gaastra and Sailworks are going with special head battens in some designs, nearly every sailmaker is producing sails with more conventionally truncated tips. That is, they’re doing what Dave Ezzy has been doing for years, which is trying to make the heads of their sails wider and less pointy while using standard battens and more conventional construction techniques. Whether these advantages are as obvious in the more recreational sails has yet to be seen, but at least the racier cambered freeride sails should show them. And whether truncated tips are palpably better in wave sails may not really matter. The fact that you can use a shorter mast for a given sail has to be a plus.

Advertisement

Boards: Construction

As the population of windsurfers has matured and become more skilled over the last ten years, demand for sandwich boards has increased immensely. At the same time, factories have geared up to produce good quality sandwich boards at competitive prices. Even a few thermoformed boards from F2 are now sporting a sandwich construction. Consequently, while one board out of ten sold may have sported sandwich construction eight years ago, in 1999 that ratio may be more like one out or three, possibly higher.

As the population of windsurfers has matured and become more skilled over the last ten years, demand for sandwich boards has increased immensely. At the same time, factories have geared up to produce good quality sandwich boards at competitive prices. Even a few thermoformed boards from F2 are now sporting a sandwich construction. Consequently, while one board out of ten sold may have sported sandwich construction eight years ago, in 1999 that ratio may be more like one out or three, possibly higher.

So what, exactly, is sandwich constuction? Simply put, it consists of layers of materials with different properties laminated together. In windsurfing boards it typically consists of layers of fiberglass cloth epoxied to each side of a sheet of PVC plastic foam. The point is to put the dense, strong materials like fiberglass on each side of a less dense, less strong core material like plastic foam, so as to produce a skin with higher strength for a given weight than would be possible with either of the components alone.

Of course, manufacturers use a wide variety of materials other than fiberglass, and the foam cores can be of different types, thicknesses and densities. Substitutes for fiberglass are “S-glass” (a stronger type of fiberglass), Kevlar and carbon fiber, while foams used typically range from 4 to 8 pounds per cubic foot in density and from 2 to 6 millimeters in thickness. Brand names for foams commonly used are “Divinycell” and “Aerex.”

What’s this mean for you, the buyer? A board with a thermoformed plastic skin is usually less costly than a sandwich board, and better at resisting dings and puctures. On the other hand, it’s usually more likely to buckle or break in half on a hard landing. This means the board with the thermoformed skin is better for the sailor with only moderate experience and skill. The sandwich boards, on the other hand, tend to be lighter and stronger overall, but more prone to denting and puncture. They’re best for experts.

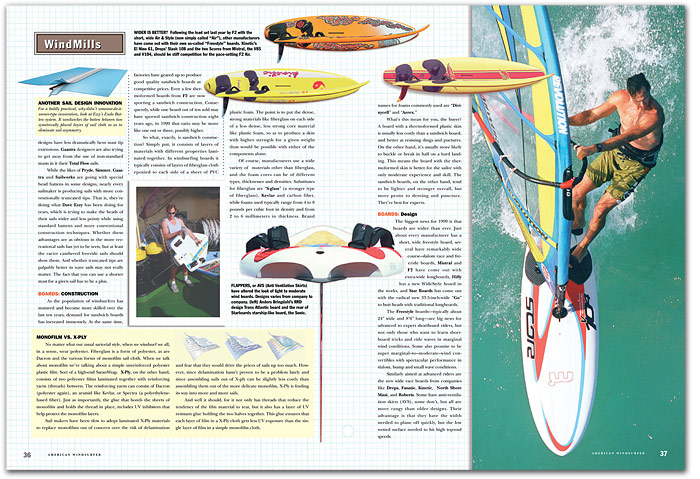

MIKE PILTZECKER, AW’s Chief Instructor and Managing Editor hangs ten in the magazine’s volume test pool. The super-wide and stable “Go” from StarBoard went through a thorough examination by the AW test team and was judged the most innovative design for 1999. Boards of this type have been in the works for a decade or more, but this particular design can be traced back three years to a meeting in Germany where members of the windsurfing industry challenged themselves to come up with a better board for novice windsurfers.

Hifly has spent the last six or seven years creating very stable, durable boards that offer incredible value to casual windsurfers. Mistral has recently come out with the inflatable WindGlider, something even wider and easier to sail for the casual windsurfer but not as fast in strong winds. Now Star Board has chimed in with a board that offers great simplicity, stability and exciting performance, together with low weight and a reasonable price. In fact, the folks at Star Board see the Go as a way to spur interest in both their products and the sport of windsurfing,

so they’re offering it at a ridiculously low price.

Boards: Design

The biggest news for 1999 is that boards are wider than ever. Just about every manufacturer has a short, wide freestyle board, several have remarkably wide course–slalom race and freeride boards, Mistral and F2 have come out with extra-wide longboards, Hifly has a new WideStyle board in the works, and Star Boards has come out with the radical new 33.5-inch-wide “Go” to butt heads with traditional longboards.

The Freestyle boards—typically about 24” wide and 8’6” long—are big news for advanced to expert shortboard riders, but not only those who want to learn shortboard tricks and ride waves in marginal wind conditions. Some also promise to be super marginal–to–moderate–wind convertibles with spectacular performance in slalom, bump and small wave conditions.

Similarly aimed at advanced riders are the new wide race boards from companies like Drops, Fanatic, Kinetic, North Shore Maui, and Roberts. Some have anti–ventilation skirts (AVS), some don’t, but all are more rangy than older designs. Their advantage is that they have the width needed to plane off quickly, but the low wetted surface needed to hit high top-end speeds.

A notch down the scale in terms of race performance, but just as quick to plane off and even easier to handle are the super-wide freeride boards from the likes of Seatrend and Roberts. In their bigger sizes—as much as 31 inches wide—they promise to be a godsend to heavy riders eager to take advantage of winds in the 8 to 18-mph wind range. The advantages of these AVS designs are not only that they have more range than any conventional board 28 to 31 inches wide could hope to have, but that they’re easy to turn.

Most of the other wide boards are aimed at windsurfers who aren’t so far along in their skills: complete beginners to advanced intermediate riders. These are the boards for windsurfers who learned windsurfing’s basics on Mistral’s inflatable WindGlider (already, after one year, the biggest selling sailing craft in the world) or the Hifly 335 and who want to upgrade to more capable boards. Their main advantages are better quickness to plane and better stability in non-planing mode than narrower designs.

The most intriguing design of the year is StarBoard’s Go. At only 9’2” long, a whopping 33.5” wide, and 176 liters of volume, it’s clearly in a category of its own. It’s a shortboard which sports a single tail fin in some versions and twin forward fins for good light-air upwind performance in other versions. Though designers for the Bics and Mistrals of windsurfing have been playing with this basic idea for over a decade, it took a small player like StarBoard to actually put it into production. The strengths of the Go are that it’s as floaty as a longboard—as stable as most and, when equipped with forward fins—as weatherly as a longboard. It has an EVA foam deck, for a cushy, comfortable feel, so that falls are unlikely to mean bruises. The kicker is that it can perform like a big freeride slalom board when the wind kicks up a little. Of course, traditional longboards can go pretty well in breeze, perhaps as fast as the Go, but the Go’s greatest strength is its simplicity. It doesn’t require the complication of a foot-adjustable mast track or foot-adjustable center board to do its thing. It has all the simplicity of shortboards together with the size and stability of a longboard. That can only be great news for novice and casual windsurfers.

Advertisement

So, having said all that, let’s consider whether change in these cases really equals improvement. Sure, designers and manufacturers earnestly think they’re making progress, but are they really? The answer has a lot to do with what you’re looking for in windsurfing. Some changes, like the Shear Tip in the Neil Pryde Z-1 sail, are clearly and unambigiously an improvement for windsurfers who want the ultimate in a fast, rangy, smooth-handling sail, and the various Freestyle boards promise to complement the quivers of accomplished wave and bump sailors—those who don’t have a whole lot of wind all the time. The super-wide race and freeride slalom boards are great for racers and marginal–to–moderate-wind freeride sailors who want boards that will get them going in less wind while remaining controllable in respectable winds. The Mistral WindGlider, Hifly WideStyle boards, wide longboards from Mistral and F2 and the Go from Star hold great promise for less experienced sailors.

In short, windsurfers who live on Maui or in the Gorge—windsurfers who do bump and wave sailing in 20 to 30-mph winds day after glorious sunny day—aren’t really going to see a whole lot of change in their equipment. For this elite five percent of American windsurfers these major trends have only something to offer: slightly more rangy and durable wave sails, and a little more variety in board construction. For the rest of the windsurfers in North America, the 95 percent who face more variable wind and less of it overall, these trends have much to offer. Improvement? On a grand scale.

Ken Winner, the technical editor at American Windsurfer Magazine, is back from a grueling five weeks of equipment testing on Maui. Check out our next issue for what he and his teams of amatuer and professional testers have to say about the 1999 high-wind and wave gear.