I WAS SITTING ON THE BEACH. The sun had come out, after days of rain. So had three young women, basking away in bathing suits that appeared to have been chosen with a self-consciousness that verged on the metaphysical. I didn’t think they were looking for men. There were so few eligible ones on the island, for one thing, and besides, this trio had the proprietary smugness of women who have decided to spend the afternoon in the World of Women.

So when a young man on a windsurfing board rounded the closest point, heading their way, I wondered if I might not witness the psychosexual equivalent of what shopping mall cops call “a situation.”

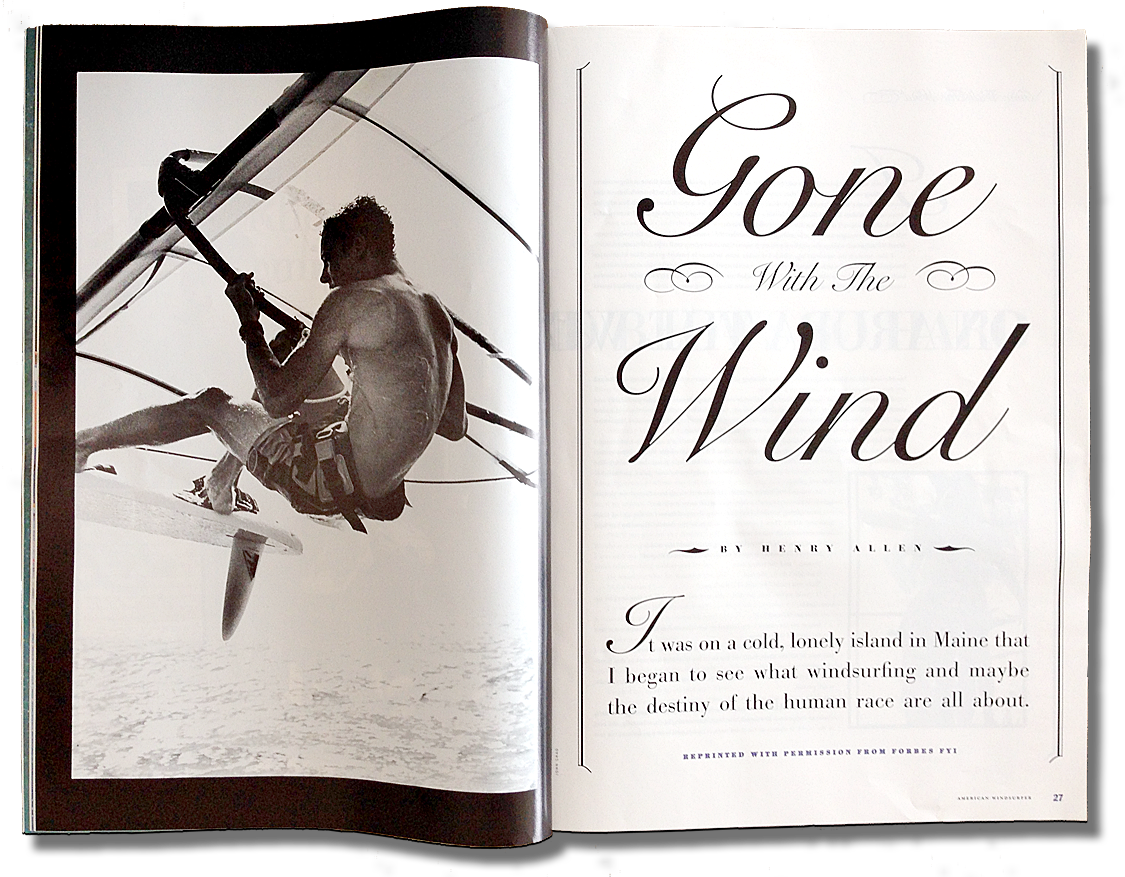

I also studied the windsurfing, which I’d never seen before. It looked great. The windsurfer lounged back from the sail, all angles, everything cantilevered off everything else, his arms extended, his body draped over the water in a curve that reminded me of urchins hanging off the sides of buses in Naples. I couldn’t think of a better way to approach three young women in bathing suits. He was blonde and tan, it became apparent. He was showing off, too–you can’t look modest on a sailboard any more than you can look modest on a unicycle.

The women looked at him and looked at each other–slow, sharp glances of modern solidarity and sisterhood. Still he beat on, a board against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the endocrinal past… Narcissus Meets the Maenads… Captain Blood bearing down on the ad hoc nunnery that exists wherever two of three are gathered in the name of American womanhood…

He coasted into the beach. He hopped off the board with the aplomb of a male who had brought home the bacon. How satisfied he looked. (In years to come I’d discovered the bizarre illusion that windsurfing inspires–that you’ve done something morally worthwhile, a good day’s work.) The women ignored him, though. It was his smugness against theirs, and neither side was giving.

He turned the board around. He shook the sail, he adjusted the center board. At last he got ready to step up and sail way in silence.

Advertisement

I was getting worried. Had something changed forever in the age of feminism and AIDS? Then I noticed the woman in the middle. Some sort of hormone seemed to be taking hold.

“Don’t you have to be awfully strong to do that?” she asked.

Her friends’ eyes went square in an astonishment of disgust.

“Noooo,” said the young man.

“I couldn’t do it,” she said.

“Sure you could,” he said. “I’ll teach you.”

“I could never, ever do that,” she said with a perkiness that verged on the cosmic.

“It’s easy. C’mon.”

Desperate for counsel, she looked to her friends, but they had turned to a careful study of the horizon.

In moments, he had her on the board, his arms around her as he showed her how to lift the mast, hold the boom of his mad and useless toy, this nautical vanity.

Yes. I thought, Faulkner was right. The human race will not merely endure, it will prevail.

On Aruba, the wind blows so hard you think something terrible is about to happen–a line squall, the Death Star coming in for a landing, the end of the world. It clatters in the palm trees, it rushes past your ears so loud the rest of the world seems hushed. It blows fifteen, twenty, twenty-five knots, month after month. There is so much wind that nobody lives on the windward side of the island, which is a little Dutch-supervised outcropping of desert fifteen miles off the Venezuela–cactus, goats, casinos for the luxury-hotel and cruise ship types, and natives driving old American cars that can still get rubber in a second, and do.

And windsurfers, with the preternatural calm of adrenaline freaks, the sort of we-luck-few entitlement you see in fighter pilots and the discoveries of psycho tropic drugs. They come from around the world for this wind, which sends the whitecaps packing across a Caribbean so pale a green that it’s more a quality of transparency than a color.

This may be the best flat-water sailing in the world–there are jumpable waves on the windward side of the island, but it’s the flat water on the leeward side that brings in the pros for the racing, and board and sail companies for their advertising shoots. If you do enough windsurfing, you are apt to end up here, the way you are apt to end up in Maui and the section of the river called The Gorge in Hood River, Oregon.

This is how they treat you when you arrive at Sailboard Vacations’ Windsurfing Village–as if it were only a matter of time before you showed up, though frankly they expected you a little earlier. If you are a weekend sailor of big, forgiving boards in light, forgiving winds, you feel wonderfully flattered.

Sponsored Links

Windsurf Village is a vaguely bohemian, isolated, post-colonial collection of one-story tropical houses and equipment sheds on the north end of the island. It caters only to windsurfers, and lets the luxury hotels a mile down the beach handle the para-sailing and piña colada custom, along with the Venezuelan princesses in the $150 Moschino thongs known to Aruba’s windsurfing pros as “butt floss.” Windsurfing Village is above all that somehow. It does not lack beautiful women hanging around–there was one during my stay who looked like the sullen, slightly overweight teenage cousin of Ingrid Bergman, and I never saw her say a word to anyone. There was a Yugoslavian with a huge, mysterious triumphal grin. But they didn’t wear thongs. Windsurf Village transcends all that–an atmosphere of offhanded, barefoot elitism.

“Drugs are addicting, sex is addicting, but windsurfing is the most addicting,”

“We’ll put you on the Bamba,” said John Doyle, the head instructor. The Bamba is a twelve-foot board dismayingly like the board I’d been sailing at home. I was only an hour off the plane, but lately I’d been thinking I was ready for a move to something smaller and livelier.

He asked me what my standard sail was.

“A 6.4 Gaastra.”

“Check out a 6.0”

I worried that John already had my number: an ex-Marine with a big ego and a tendency to view my relationship with a nature as a grudge match; a slow learner with a low tolerance for frustration.

“Make it a 5.5,” he said.

He explained about the off-shore wind, and how it can blow you over the horizon if you’re too egotistical, stupid or frustrated to wave for help. He seemed to sense my weakness for irony. As we walked across a two-lane road to the beach, he administered a coup de grace: “Always look both ways before you cross,” he said.

I waded out to my board with my 5.5 sail.

It was getting late and up and down the beach, at the various windsurfing places, the pros were coming our to sail after a day of teaching. I watched.

They flew along with the cool, desperate panache of James Dean riding on the top of the train in East of Eden.

They carved into their jibes–the carved jibe being one of the fine moments of sport, like a good double play of a well-jumped fence– tilting their boards through downwind turns, leaning forward motionless and perfect as hood ornaments, and then with a gesture as delicate and casual as a French waiter doing one of those fork-and-spoon moves with the veal, they tossed sails around bows and planed away.

Step jibes, duck jibes, all of them part of the species called the carved jibe, in which the board reverses direction without ever coming off a plane. Once in a while, I spotted a laydown jibe in which the sailor swept the sail across the water like a bullfighter spreading his cape of a blackjack dealer fanning our a six-deck shoe. I had heard of these things and wondered just what was the point. I saw now that the point was a conspicuous freedom and gratuitous beauty, executed with an immodest pointlessness that verged on the gorgeous. What fence can Tom Sawyer walk for Beck Thatcher anymore? Where is Cary Grantian grace that has not been expunged by the puritanism of consensus? It is in the windsurfing. Now, with my smallish sail hooked into my largish board, it was my turn. I noticed myself thinking: this is more wind than you’re used to. Don’t you have to be awfully strong…

I stepped up on the board in a beach start, rounded up and got slam-dunked and ended with the sail over my head. I tried again. Fell again. I decided to pull the sail up with the uphaul rope instead, a step back on the learning curve. I stuttered-stepped around the board like a man with a back problem trying to put out a grease fire. I stalled the sail. I hoped John wasn’t looking.

Advertisement

All around me, sails flashed past, the windsurfers leaning back in their urchin slouch. In the words of the half-mat Scotsman who taught me to sail, “In sailing, you must drink deep from the cup of humiliation.” In a moment, the cup’s rim was touching my nose as the last drops rolled out. I hooked into my harness line, in hopes of cranking up a respectable plane. I caught a lull. I straightened my knees. Then a puff hurled me over the sail in the trajectory that resembled a plague-ridden corpse being catapulted into a medieval castle–this maneuver is known, in fact, as a catapult, and I would go on to break to masts in two days doing it–a Windsurfing Village record. At last, I found myself standing in waist-deep water on a sandbar, a long way down the shoreline from Windsurf Village. I would have to sail back. I climbed on the board. The hell with it. Just get back, and find a good restaurant. I uphauled. I accelerated to big, crazy speed, tail-walking like a hungry porpoise at Marineland. I hung on. I hoped John was looking. In a matter of seconds, I could remember why windsurfers keep saying that it’s better than sex, why they call it an addiction.

“Drugs are addicting, sex is addicting, but windsurfing is the most addicting,” said a forty-four-year-old psychiatrist name Wayne Phillips, from Boulder Colorado. It was days later, and I was sitting on the breakfast patio with Wayne, watching the whitecaps gather on the water, listening to the palms rattle, feeling the odd, small fear that precedes a day on the water when the wind is really cranking.

He said: “I happen to prefer being scared to being bored. We’re designed to handle extreme stress, we’re a warlike species, our whole limbic system is set up for this. I bet you have a lot of people with mood disorders who need to get out of them, and windsurfing does it. It feels like you’re doing something terribly important but I’ve never figured out why. I mean, this is really crazy, I’m ending up with a lot of pain here.”

“Yes,” I said.

He held up hands wrapped with adhesive tape to cover blisters and sores. I lifted my feet to show a couple of yards of tape.

“You have this sense of mastering the unmasterable. I remember the first time I planed–I was at the Boulder reservoir on a twelve-foot board when I first started. The wind started coming up. I didn’t know what to do. I’d heard you were supposed to step back and lean, so I did, and suddenly it was like I’d entered another world, the lake had turned to glass.”

I have a story like this too, about a squall hitting my beginner board in North Caroline. Everybody has one. You remember these things: first a plane, first harness ride, first waterstart, first shortboard ride, first shortboard jibe…another world. No doubt the long-muscled Hawaiian youths you see on television sports shows remember their first loops, the board and its fifteen-foot mast doing first barrel rolls, Immelmann turns and forward and backward flips. And the crazed Frenchman who do the long-distance-crossings remember their first seas and their first friends to disappear forever, Windsurfing is a sort of ongoing rite of passage. You do it for its own sake. It doesn’t have any other sake.

It doesn’t come with anything closer to an aprés-ski scene than standing around the back of somebody’s van, drinking beer. There are no blazers of clubs with the word “Corinthian” in their name, no greens committees or tennis whites. Like a lot of sports associated with the upper classes–trout fishing, riding, fending off tradesmen’s bills–it takes years to learn, but there’s no social cachet when you get there. No matter. The windsurfers who come to Windsurf Village may be surgeons, developers, economists and entrepreneurs, big egos with big money, some of then, but they savor the slightly déclassé aspects of windsurfing. They may have van-loads of equipment back home, thousands of dollars spent on a couple of good boards, a quiver of sails, a few masts…all of it producing no more prestige than a reputation for a kind of vagabond ballsiness.

Don’t you have to be awfully strong…

Diary Entry: “Changed down to the Rumba, a ten-foot board, and my life became hell again. I got stuck by the video tower, I got stuck by Fisherman’s huts, I couldn’t uphaul, I couldn’t beach start.

“After lunch, a lesson with John. I stretched out my arms, I committed to the harness, all the way back. The board felt good and right.

“John sailed behind me: ‘Forward! Forward! Sheet in! Arms straight! Hook! Hook!’ The board danced, the board flew. This is the thrill of hooking a freight, the amazement of hitchhiking when you get a good ride. I felt like the world was mine, the way you feel when that New York is yours when you raise your hand and a taxi is there, just like that.” The learning curve is steep, but the view of every rest stop is terrific. The problem is the backsliding.

Waterstarting, for instance. Instead of climbing on the board and hauling the sail up with the uphaul rope, you tread water next to it, lift the mast into the wind, put a foot up on the board, throw the sail forward and then sail yourself up onto the board.

You have to learn this if you want to sail short boards in high winds, and you’re in water too deep to step up on the board in a beach start, and uphauling is difficult. Uphauling gets difficult when the board gets short, ultimately so short that it sinks if you stand on it without sailing. And in good shortboard winds, an uphauled sail can cavort like a captured zoo animal before the era of tranquilizer guns.

When you’re ready to learn the waterstart, a good teacher can have you doing it in one day. (One Japanese visitor to Windsurf Village got his lessons out of order and learned to waterstart before he could really sail, thereby becoming a favorite of wipe-out aficionados.)

…you notice you can think about windsurfing during sex, but you rarely think about sex during windsurfing.

Ah but the next day, I found, it was no so easy. Or the day after that, until it became a shameful secret.

“Tomorrow, we’ll go out beyond the reef and work on getting you back in the straps, fully powered up,” John said one day on the sandbar. “Beyond the reef?” I asked. “I still can’t waterstart. I tried it fifty times this morning and you know how many I got? Two. I feel like a twelve-year-old who still wets his bed. And I am fed up with practicing water starts. I hate it.”

“Let’s practice water starts.”

“No.”

“Over there, where the water is over your head.”

I tried one.

“Let me show you what you’re doing wrong,” he said. He did a waterstart. It looked perfect to me, except that he ended up like I did, being dragged along like a Viet Cong body behind an armored personnel carrier.

“You’re pulling down with you front arm,” he said. “You’re trying to pull yourself up on the board.”

Of course. Don’t you have to be awfully strong to do that? No. The trick is to get up by not pulling yourself up. Where are the Zen Buddhists when you really need them?

I positioned the sail, got a foot up on the board and then tossed my front art forward with all the languor of a woman throwing rice at a bride she doesn’t like very much.

And I rose like a god from the sea and sailed away frantic with self-congratulation. I even did it again.

“Windsurfing is simple,” said John the Ironic. “But it’s not easy.”

The days went along as they do in the tropics, impossibly fast and slow at the same time.

Evenings, we’d eat wahoo and plantains and Jamaican jerk ribs in restaurants where the windsurfing bums eat, drink Dutch beer and the best white wine-by-the-glass I have ever drunk.

We talked about windsurfing, and how you know when you’re addicted: you watch some horrible Yugoslavian massacre on the TV news but all you see is the trees blowing in the background, twelve-fourteen knots, rig the 6.2; you notice you can think about windsurfing during sex, but you rarely think about sex during windsurfing.

We talked with the happy stupidity that windsurfing induces, a mental state that can have a MBA stockbrokers talking in noises like teenagers: “So I’m carving around kkkyyyeeewwww, and I hit the chop bap bap bap…”

A study from a German company named Gun Sails says that there are over four million boardsailors in both France and Germany, but only 1.7 million in America. Why? Windsurfing confers freedom. No lift tickets, no yacht club membership necessary. Ah, but freedom is what Europeans want more of, and Americans seem to be tire of. On the other hand, it confers speed, and Americans can’t get enough of that. Windsurfers are the fastest wind-powered thing on the water–they’re going over 50 miles an hour now.

I tried to explain my theory that the lure and the dread of windsurfing lie in variables.

There are a lot of variables that only exist when they’re put together in a system, in a manner of a computer or a rain forest.

Consider the fact that you’re learning to sail a boat where not just the sail and the boom but also the mast moves, rotating on a universal join–it was this universal joint that was the inspiration of windsurfing’s inventors in the early 1960s in California. The universal made it possible to steer by moving the sail back and forth, instead of using a rudder–direction became a variable of sail position, in other words.

Then consider the paradox that velocity and position are variables of each other in windsurfing.

You see this is as you move from twelve-foot boards down toward the eight-foot boards of the wave jumpers and the slalom racers, the ones that sink unless they’re moving fast enough to plane. Velocity equals position here, V=P. Simple, but not easy. Everything in windsurfing–velocity, position, board, sail, skeg, wind, water, skill level–is a variable of everything else, with not definable integrity as a system until it’s up and sailing. A quarter horse or a sailboat has its own integrity, with or without somebody on it. Mess with just one variable in a windsurfing system and the whole thing collapses into the water with the integrity of a shotgunned pelican.

…I fell, of course. But I remember that feeling. I think about it often. Except, of course during sex.

Diary Entry: Shlogging along. Andy Mack (a fifty-six-year-old New Hampshire apple farmer turned windsurfing pro) raised my boom, moved my harness lines back, took my board out for a test run, left me with his Electric Rock, eight feet eight inches, with his own 6.0 monofilm sail. I didn’t want to catapult and put my head through his sail but I couldn’t resist. Waterstarted. Lovely nimble speed on this little thing, felt like Fred Astaire tap dancing out through the chorus.

‘Hey what were you sailing down there in Aruba?’

“Eight-and-a-half foot board.”

Still, I had not carved a jibe. There was no chance, in fact, that the carved jibe would be mine in anything like the near future, or even the middle-distance future. It can take a decade.

Nevertheless, my last morning at Windsurf Village, the wind was cranking. I went out on a nine-foot board with a 5.0 sail. A lot of wind, the biggest of my stay, hammering me bad for a few minutes until it came together, simple, if not easy…lounging out over the water, front foot in the strap, the board accelerating like a big motorcycle, that feeling of everything flattening out, loosening, escaping… What the hell. I pressed down the leeward rail, leaned forward, felt the board carve around fast enough that it had centrifugal force…I think I also sensed that moment when you’re supposed to toss the sail around and plane off again, the moment when everything is perfect and easy and the French waiter serving the veal…

I fell, of course. But I remember that feeling. I think about it often. Except, of course during sex. I’ll work on it, on the short board I bought as soon as I got back from Aruba. I will not merely endure, I will prevail. When I do, maybe I’ll confess that you don’t really have to be awfully strong to do it. But maybe I won’t.

Windsurfer Henry Allen was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 2000 for his writings in the Washington Post on photography