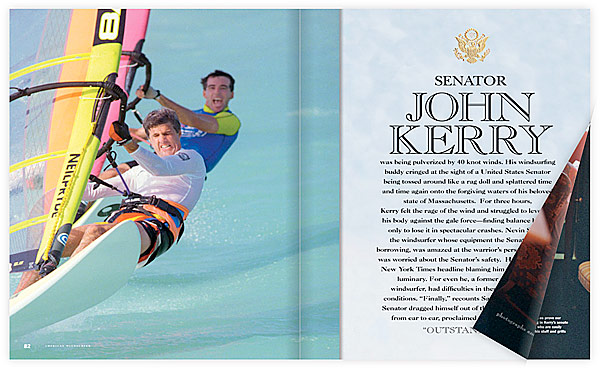

SENATOR JOHN KERRY was being pulverized by 40 knot winds. His windsurfing buddy cringed at the sight of a United States Senator being tossed around like a rag doll and splattered time and time again onto the forgiving waters of his beloved state of Massachusetts. For three hours, Kerry felt the rage of the wind and struggled to leverage his body against the gale force—finding balance briefly, only to lose it in spectacular crashes. Nevin Sayre, the windsurfer whose equipment the Senator was borrowing, was amazed at the warrior’s perseverance and was worried about the Senator’s safety. He could see the New York Times headline blaming him for the loss of a luminary. For even he, a former professional windsurfer, had difficulties in these overpowering conditions. “Finally,” recounts Sayre, the 54–year old Senator dragged himself out of the water and, grinning from ear to ear, proclaimed the experience as . . . “OUTSTANDING!”

Advertisement

TRUE GRIT “Kerry fights us and makes us prove our point” says staffer Jim Jones (standing in Kerry’s senate office). “He’s not like some Senators, who are easily directed by their aides. Kerry knows his stuff and grills us on every issue.”

SENATOR JOHN KERRY sat at the head of a conference table. I watched from the side of the room. To his left was Governor Tom Carper of Delaware and surrounding them were lawyers, lobbyists and various representatives from Amtrak. They were gathered at Kerry’s senate office to discuss issues that were holding up the passage of the Amtrak Reform and Accountability Act of 1997. Kerry listened intently. I saw him pick up on the words, but more importantly I knew he heard the sounds, catching weakness in subtle hesitations or strengths from the voices of the lobbyists. [I know this because in the many conversations I’ve had with John Kerry, he has exhibited an uncanny ability to catch vocal tones that reveal one’s true disposition. He picks up on tones and verbally questions or reflects upon them with profound accuracy.] When the arguments were presented, Kerry spoke with authority. His voice has a deep resonance of intelligence and weight; it’s a voice that commands attention. He pinpointed the strengths and weaknesses of the arguments and in a shepherd-like manner, he masterfully synthesized the opposing arguments to a point of seamless balance. “I have never seen anyone grasp issues as quickly as this man,” said Gregg Rothchild, one of Kerry’s many legal aides. “It is amazing how he can bring people together to a common denominator.” I watched in awe. A room full of hard core politicians and lobbyists with vested interests were brought together to a point of sensible compromise. The Amtrak bill passed a week later.

JOHN KERRY waded upwind at the event Site in Hood River, Oregon. It was mid-afternoon and the Senator had been struggling with unfamiliar equipment in an unfamiliar territory since 9:00 AM. As far as the windsurfers on the Columbia River Gorge were concerned, Kerry was just another ordinary windsurfer trying to find balance in the shifting winds of the day. With him were Olympic champion Mike Gebhardt and Sam Grossman, a windsurfing friend who flew in with the Senator that morning. It takes an average windsurfer a day or two to acclimate themselves to the Gorge’s extreme conditions. John Kerry did not have that luxury. Gebhardt, a three time Olympic Champion, sailed with the Senator all morning, barking instructions at him. Later in the afternoon, Gebhardt and I rested on the bank watching Kerry drag his equipment up wind for the umpteenth time— we marveled at the man’s endurance. “You know, not many people from his position of power and wealth would put up with this kind of humiliation,” said Gebhardt to me.“You really feel stupid having someone like me yelling instructions at you. It’s degrading, you feel like a school kid . . .This sport is incredibly humbling and it’s great to see a guy like that out there trying! Really impressive!” When we bade farewell that afternoon, Kerry’s exuberance was unmistakable. With a youthful dragon-slayer’s delight written all over his face, John Kerry made me feel like I’d just witnessed the best day of his life. However humbling or frustrating it may be, this man clearly thrives on challenges, has the capacity to endure, and can elevate his skills to match the foe.

It was 1996, during a tight race between John Kerry and Governor Bill Weld for the Senate seat that Kerry had held for the previous two terms. The two Bay State giants were beating each other up badly in a desperate battle for the seat. To prepare their candidate for a series of debates Kerry’s staff brought in political consultant Bob Schrum to help in the final two month of the campaign. The challenge was to take whatever provocations the opposition threw at him and turn them into his own message. Bruce Droste, Kerry’s brotherly best friend, sat and watched the preparations and thought to himself, “This is brutal!” Afterwards, in the car, Droste noticed Kerry’s countenance and asked, “Johnny, are you OK?” Kerry turned to Droste and replied, “You know, the negativity of the last weeks is not fun. This is not the way it should be. This [process] is distasteful.” The two men looked at each other and with a nod, acknowledged the brutality that politics has on human sensitivity. Kerry went on to win the toughest and most expensive election of his career, a race that cost each camp 12 million dollars. [During his celebrated acceptance speech and shortly after the bitter battle that saw Weld’s team attack very personally, John Kerry rose above the storm and invited Bill Weld to join him at a local pub so that they could put the past behind them by having a beer of civility.] Six months later, Weld made a bid for the ambassadorship to Mexico—a move that unfortunately brought his political career to a screeching halt. Firmly planted in his way was an intransigent and powerful Jesse Helms, who refused to open the door for a simple hearing. Seeing the injustice, Kerry could have easily stayed in the background. Instead he stood up against the potent Helms and wholeheartedly came to the aid of Weld — his 12 million dollar foe.

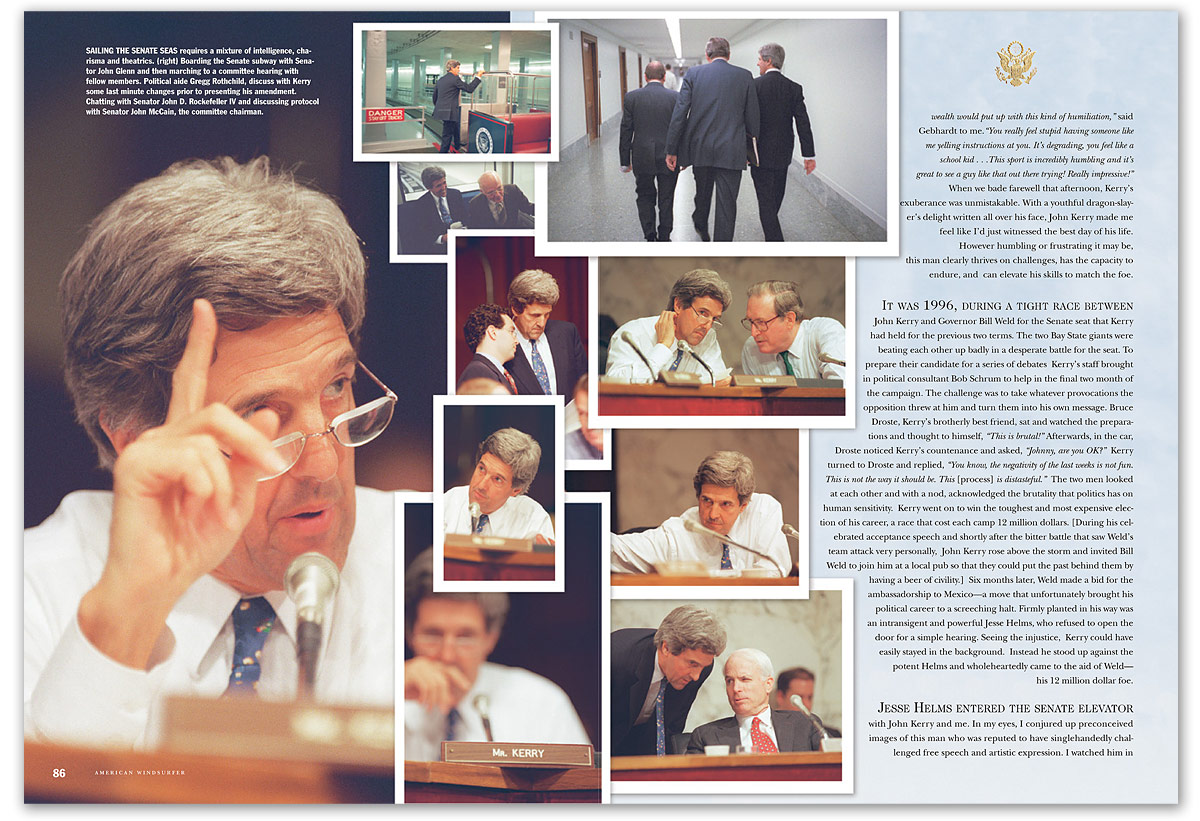

SAILING THE SENATE SEAS requires a mixture of intelligence, charisma and theatrics. (right) Boarding the Senate subway with Senator John Glenn and then marching to a committee hearing with fellow members. Political aide Gregg Rothchild, discuss with Kerry some last minute changes prior to presenting his amendment. Chatting with Senator John D. Rockefeller IV and discussing protocol with Senator John McCain, the committee chairman.

Jesse Helms entered the senate elevator with John Kerry and me. In my eyes, I conjured up preconceived images of this man who was reputed to have singlehandedly challenged free speech and artistic expression. I watched him in silence—a silence that could have easily continued without acknowledgement. To my right, Senator Kerry broke in and said something I can’t recall and Jesse Helms responded. Again, I can’t recall the words but I remember the tone—a tone that surprised me. There was a familiarity to their voices, a tone of respect, of understanding and even affection. After their brief exchange, Kerry introduced me and I shook hands with the legend. As we greeted, I looked into his eyes and caught sight of a frail and elderly statesman. Something changed in that brief encounter—something which made me realize, in retrospect—John Kerry does not burn his bridges. No matter how bad the battle rages, there is a clear truce of civility that binds these political gladiators.

The Viet Cong snipers were regularly taking pot shots at his Navy gun boat known as a PCF—a Patrol Craft Fast or Swift Boat. The 25-year-old commander of PCF-94 was getting pretty fed up. He and his crew of six were part of an operation known as Sealords—the Navy’s daring plan to penetrate the dangerous but vital waterways of the Mekong Delta. Like scenes from Francis Ford Copola’s Apocalypse Now, the swift boats became prime targets for the ambush-minded Viet Cong lurking in the dense jungle lining the river banks. Quietly, John Kerry formulated a battle plan to confront the threat and waited for the right moment. Then one day, when Kerry was in command of a three boat raid, bullets came flying from mangroves on the side of the river. Kerry turned his swift boat 90˚ to the right and ordered the others to follow full speed into the heart of the ambush. He rammed his boat onto shore and with his crew, chased the enemy on foot until they were eliminated. A few moments later, while investigating gunfire a little further upstream, a rocket blast blew out all the windows in the mid part of the boat. Kerry beached again in the middle of the ambush and routed the enemy the second time. This strategy was a change from previous Swift boat engagements which had almost always resulted in a quick firefight and retreat. When news of the heroic deed (and that not a single man under Kerry’s command was wounded) reached Admiral Elmo Zumwalt, Commander of Naval Forces Vietnam, the Admiral put Kerry up for our country’s second highest honor, the Navy Cross. “It was an act of bravery beyond the call of doctrine,” said the now retired Admiral. But then, to impact moral, the Admiral decided to by-pass Washington’s approval for the Navy Cross and flew immediately to the Delta where he awarded Kerry the Silver Star and decorated each of the men who participated in the raid. It was his act of personal respect for the leadership Kerry had exhibited.

Advertisement

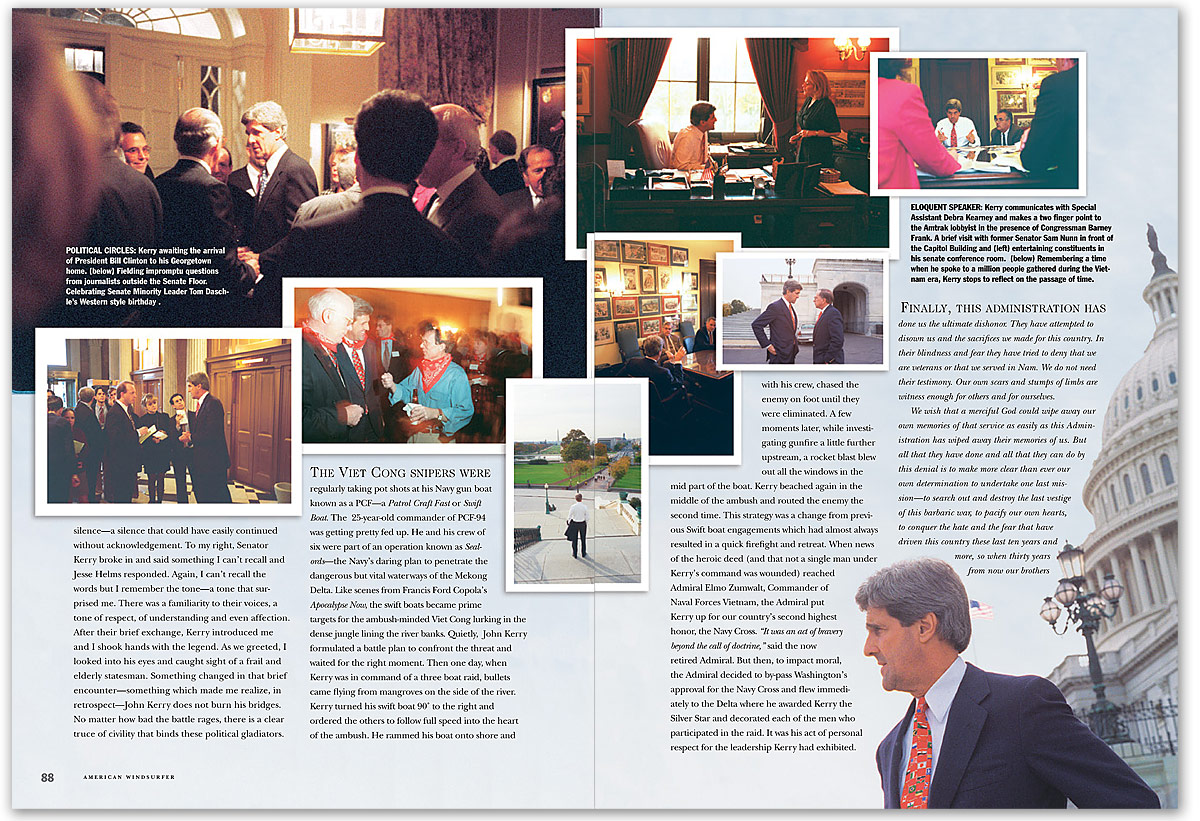

POLITICAL CIRCLES: Kerry awaiting the arrival of President Bill Clinton to his Georgetown home. (below) Fielding impromptu questions from journalists outside the Senate Floor. Celebrating Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle’s Western style birthday .

ELOQUENT SPEAKER: Kerry communicates with Special Assistant Debra Kearney and makes a two finger point to the Amtrak lobbyist in the presence of Congressman Barney Frank. A brief visit with former Senator Sam Nunn in front of the Capitol Building and (left) entertaining constituents in his senate conference room. (below) Remembering a time when he spoke to a million people gathered during the Vietnam era, Kerry stops to reflect on the passage of time.

FINALLY, THIS ADMINISTRATION HAS DONE us the ultimate dishonor. They have attempted to disown us and the sacrifices we made for this country. In their blindness and fear they have tried to deny that we are veterans or that we served in Nam. We do not need their testimony. Our own scars and stumps of limbs are witness enough for others and for ourselves.

We wish that a merciful God could wipe away our own memories of that service as easily as this Administration has wiped away their memories of us. But all that they have done and all that they can do by this denial is to make more clear than ever our own determination to undertake one last mission—to search out and destroy the last vestige of this barbaric war, to pacify our own hearts, to conquer the hate and the fear that have driven this country these last ten years and more, so when thirty years from now our brothers go down the street without a leg, without an arm, or a face, and small boys ask why, we will be able to say “Vietnam” and not mean a desert, not a filthy obscene memory, but mean instead the place where America finally turned and where soldiers like us helped it in the turning. On April 22, 1971, Kerry testified with these words before a special session of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. It was a tension filled room flooded with supporters of the war as well as those against it. Seated in front of the committee was John Kerry. The Republicans on the committee were making moves to block Kerry’s speech and the tension mounted as the arguments rang back and forth. Suddenly, Senator William Fulbright from Arkansas spoke. “Mr. Kerry, would you move the microphone please.” A dead silence embraced the room. “We thought that Fulbright was telling John he couldn’t speak,” recalled Geoge Butler, a supporter of the Peace Movement and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War. [Butler later went on to make the film “Pumping Iron” with Arnold Schwarzenegger and pioneered windsurfing in the state of New Hampshire.] At the peak of the silence, Senator Fulbright broke in again and said, “How many medals are you wearing Mr. Kerry? Is that a Silver Star and a Bronze Medal and three Purple Hearts that I see hidden by the microphone?” Suddenly, the rising tension in the room was skillfully directed to Kerry and what he was about to say. “He was a hero, a highly decorated naval veteran that had come home and turned against the war,” said Butler, “Afterwards, CBS interviewed him on the air for 10 minutes and Kerry became an icon for the Peace movement. He was eloquent and articulate and he could gracefully tell you the reasons he was against the war. It was a turning point in the anti-war movement.” How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake? —John Kerry

“THE PHONE RANG ON SUNDAY MORNING and it was John,” said Bruce Droste, Kerry’s friend. “He said, ‘Get your suit on. We’re going to church.’ This was the Sunday after Rodney King’s verdict and the Watts riot.” An hour later, Kerry met Droste and they drove to the 12th Baptist Church, the heart of Boston’s black community. “Why are we doing this?” asked Droste. “Because it’s the right thing to do. People are hurting and I want to show my respect and support,” replied Kerry. They were seated towards the front of a church whose only white parishioner was a man in the choir. Reverend Michael Haynes came over during the singing of a hymn, greeted Kerry and asked if he would like to address the congregation. Kerry declined and said he didn’t come to speak but was there to show support. Still the Reverend insisted that it would be nice if he said a few words. Kerry asked when he should talk and the Reverend said, “After this hymn.” “John had studied religion, so he grabbed the Bible, looked up a passage, reviewed the scripture, got up and proceeded to give a 10 minute sermonette. By the end I looked back and all the women in the row behind me had tears in their eyes,” observed Droste. “It was incredibly moving!”

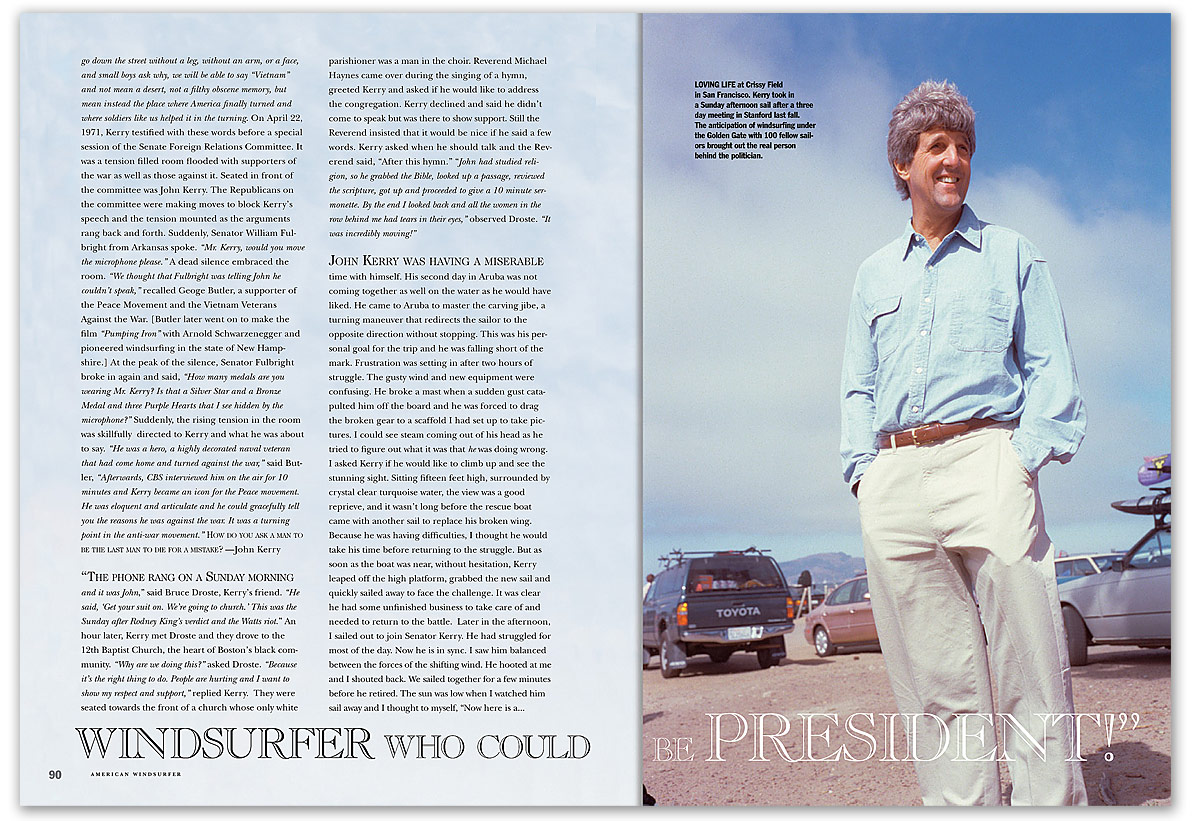

LOVING LIFE at Crissy Field in San Francisco. Kerry took in a Sunday afternoon sail after a three day meeting in Stanford last fall. The anticipation of windsurfing under the Golden Gate with 100 fellow sailors brought out the real person behind the politician.

JOHN KERRY was having a miserable time with himself. His second day in Aruba was not coming together as well on the water as he would have liked. He came to Aruba to master the carving jibe, a turning maneuver that redirects the sailor to the opposite direction without stopping. This was his personal goal for the trip and he was falling short of the mark. Frustration was setting in after two hours of struggle. The gusty wind and new equipment were confusing. He broke a mast when a sudden gust catapulted him off the board and he was forced to drag the broken gear to a scaffold I had set up to take pictures. I could see steam coming out of his head as he tried to figure out what it was that he was doing wrong. I asked Kerry if he would like to climb up and see the stunning sight. Sitting fifteen feet high, surrounded by crystal clear turquoise water, the view was a good reprieve, and it wasn’t long before the rescue boat came with another sail to replace his broken wing. Because he was having difficulties, I thought he would take his time before returning to the struggle. But as soon as the boat was near, without hesitation, Kerry leaped off the high platform, grabbed the new sail and quickly sailed away to face the challenge. It was clear he had some unfinished business to take care of and needed to return to the battle. Later in the afternoon, I sailed out to join Senator Kerry. He had struggled for most of the day. Now he is in sync. I saw him balanced between the forces of the shifting wind. He hooted at me and I shouted back. We sailed together for a few minutes before he retired. The sun was low when I watched him sail away and I thought to myself, “Now here is a windsurfer who could be president.”

Continue to INTERVIEW: